In the spring of 2020, I wrote this blogpost for WS 340: Sex, Power, and Politics, taught by Dr. Holloway Sparks. In this essay, I was instructed to explore a policy issue and analyze its gendered impacts. This post demonstrates my ability to analyze differing activists’ strategies and policy recommendations and understand their impacts on different populations. Moreover, within the context of this assignment, I was able to communicate the basics of these complex approaches to my peers, who had not studied the same topic, to help them understand the impacts of these strategies. Content Warning: this essay includes general references to sexual violence and r*pe.

In the span of a single year, just under 1% of the United States population is incarcerated (Kaeble and Glaze). Though this might not seem high, this equates to over 3 million people cycled through holding cells, city jails, and prisons in just 12 months. Some of these cases are for a night or two, while others are imprisoned for many years. With so many people coming into contact with the criminal punishment system, nearly every American knows someone who has spent at least one night in a cell. Transgender people, however, face an incarceration rate more than double that of cisgender Americans (Kaeble and Glaze). Once incarcerated, they face more violence than cis prisoners from both other inmates and prison staff. Prisons and other correctional facilities are overwhelmingly dangerous for criminalized trans people (The Editorial Board).

There are two main approaches to combating the violence against trans people in prison: radical movements that call for prison abolition and more mainstream reform efforts. While the modern gay rights movement began with explicitly abolitionist undertones (few would accuse Marsha P. Johnson or Sylvia Rivera of being reformists), neoliberal strategies of representation and market participation have become the face of the LGBT movement in recent years. The Human Rights Campaign, GLAAD, and the National Center for Trans Equality take a more reformist approach to trans liberation, while grassroots organizations like the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, Critical Resistance, and Southerners On New Ground focus on the long-term goal of abolition and complete liberation from criminalization and state violence. Both of these approaches have done work that makes some trans people’s lives more livable, and this essay is not an attempt to create a false binary between “good” and “bad” strategies. Instead, it is my hope that this will encourage readers to think more critically about mainstream LGBT movements and consider the possibilities of abolition in their relationships, municipal governments, and nations.

Most broadly, reform efforts primarily focus on working within the existing system to protect those most harmed by the same. In the case of incarcerated transgender people, reformist tactics describe lawsuits that win marginally more protections, trainings for corrections officers on trans, intersex, and GNC people, and housing for trans people that matches their gender identity rather than assigned sex at birth (See the National Center for Trans Equality’s 85 page list of proposed reforms for more). A prominent example of a reformist win is the passing and implementation of the Prison Rape Elimination Act, or PREA. Legal scholars say it signaled that “public officials could no longer ignore the problem of sexual abuse in our nation’s penal system,” but PREA purported to do much more (Gilna). The National Center for Transgender Equality writes:

The PREA regulations include several specific protections for LGBTQ individuals, such as consideration of a person’s LGBTQ identity or status in determining risk for sexual victimization, limitations on cross-gender searches, and special considerations for housing placements of transgender and intersex individuals. (10)

According to reformist aims, PREA should have been a widespread source of protection for LGBTQ inmates. And yet, trans people still face violence and harassment. Every single LGBTQI+ respondent to one survey reported being strip searched by prison staff, meaning that 100% of these inmates experienced sexual violence at the hands of prison officials (Lydon et al.). Self-reported data compiled by the Bureau of Justice found that trans inmates were 10 times more likely to be sexually assaulted by other prisoners in 2011 (Beck et al.). In some jurisdictions, PREA has actually been used to regulate incarcerated people’s presentation by disciplining those who fall outside of gender norms, while LGBTQ+ prisoners have described being punished for consensual same-sex activity (Idaho Department of Corrections 5; Lydon et al.). All of this occurs while violence against trans people escalates, with murders of trans women continually rising through 2016 and 2017 (“Violence Against the Transgender Community in 2017”). Within and outside prison walls, the prison industrial complex fails to protect trans people, particularly trans women.

Abolitionists face the failures of the criminal punishment system head on by recognizing its role in perpetuating violence against trans people and seeking to end both the need for and the usage of prisons. Their tactics include defunding prisons and police departments, stopping the construction of new prisons, and raising money for bail for poor LGBTQ people and/or people of color. Queer and trans abolitionists object to many reformist approaches on the grounds that they merely increase the power of the state to harm trans people (Bassichis et al.). Recognizing the state’s ability to shift and accommodate assimilationist demands while retaining its power to harm marginalized people (for example, by enacting hate crime laws that expand prosecutorial power), they do not see reform efforts as successful. By defining prisons as inherently violent and built to harm those on the margins of society—Black, brown, undocumented, trans, queer, and disabled people—abolitionists begin at the root of the problem rather than simply addressing the results.

We see the abolition of policing, prisons, jails, and detention not strictly as a narrow answer to “imprisonment” and the abuses that occur within prisons, but also as a challenge to the rule of poverty, violence, racism, alienation, and disconnection that we face every day.

Bassichis et al.

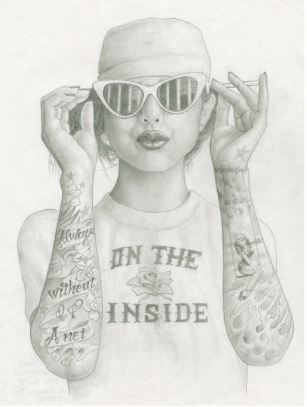

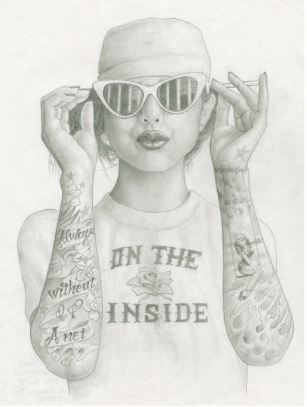

Black and Pink also displays art by incarcerated trans people in exhibitions to build support and compassion for the prisoners.

Black and Pink, an explicitly abolitionist movement that works to advocate for LGBTQI+ individuals living with HIV and AIDS within the prison system, published a report in 2015 with recommendations for ending violence against LGBTQI+ people in prison. “Coming Out of Concrete Closets” demanded the end to criminalization of sex work, racial profiling, and stop and frisk policies with actionable limitations on police power to limit the number of vulnerable people entering prisons in the first place (Lydon et al.). Sourced from LGBTQI+ prisoners, the report also encourages prisons to allow trans prisoners to communicate with others outside of their unit, contact mental health professionals via unrecorded hotlines, and receive fair compensation for their labor while incarcerated (Lydon et al.). The ultimate goal, explicitly stated under “long-term” objectives, is abolition, and reforms should have the clear and defined purpose of realizing that goal through building the strength of incarcerated trans people to advocate for themselves and connect with others. (See also Janetta Johnson, executive director of the abolitionist organization Transgender, Gender Variant, and Intersex Justice Project, discussing her own experiences that led to a reentry program for trans women.)

Reformist approaches rely on mainstream perceptions of the criminal justice system as well-intentioned and fair with a few aberrations rooted in individual prejudice. Abolitionists challenge these “dominant narratives about the carceral state,” believing that such work “broadens and sharpens abolitionist analytical vantages” (Brown and Schept). Abolitionists believe that the criminal punishment system will never provide justice for those who exist on the margins of society, while reformists attempt to find this ideal through new legislation and procedural shifts. There may be a time for both approaches, but historically abolitionist movements have gained more for and provided more direct services to marginalized people, particularly trans folk often left behind by mainstream LGBT nonprofits. The Compton Cafeteria and Stonewall Inn riots were direct action that confronted police brutality, the National Bail Out provides bail funding to poor Black people, and the Solutions Not Punishment Collaborative conducts original research to inform policy recommendations to decriminalize sex work. Abolition takes place in many forms and is focused on not just what is, but what can be. It imagines a world free of concrete closets and cages. This is where trans liberation can occur, and if reform strategies get us incrementally closer, then so be it. Reformist LGBT movements should be careful, however, not to inadvertently expand the power of their oppressors in the meantime.

Bassichis et al. “Building an Abolitionist Trans and Queer Movement With Everything We’ve Got.” Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex, edited by Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith. AK Press, 2015, 195-210.

Beck, A. J., Berzofsky, M., Caspar, R., & Krebs, C. “Sexual Victimization in Prisons and Jails Reported by Inmates, 2011–12.” Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2013. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ svpjri1112.pdf.

Brown, M., & Schept, J. “New abolition, criminology and a critical carceral studies.” Punishment & Society, vol 19, no 4, 2017, 440–462.

Gilna, Derek. “Five Years After Implementation, PREA Standards Remain Inadequate.” Prison Legal News, 2017.

“Human Rights Campaign President Speaks Before CNN Town Hall.” Uploaded by CNN, 10 Oct. 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W0JqL0dSgVI.

Idaho Department of Corrections. Procedure Control No. 325.02.01.001, Prison Rape Elimination. 2009.

Johnson, Janetta. “Janetta Johnson: Advocate and Formerly Incarcerated Person.” Uploaded by VeraInstitute, 10 June 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_R4KQwmmPjI.

Kaeble, D. & Glaze, L. “Correctional Populations in the United States, 2015.” Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2016.

Lydon, Jason, et al. “Coming Out of Concrete Closets: a report on Black and Pink’s national LGBTQ prisoner survey.” Black and Pink, 2015.

National Center for Transgender Equality. “LGBTQ People Behind Bars: A Guide to Understanding the Issues Facing Transgender Prisoners and Their Legal Rights.” 2018, Available at: https://transequality.org/transpeoplebehindbars

The Editorial Board. “Prisons and Jails Put Transgender Inmates At Risk.” The New York Times, 2015.

“Violence Against the Transgender Community in 2017.” Human Rights Campaign. 2017.