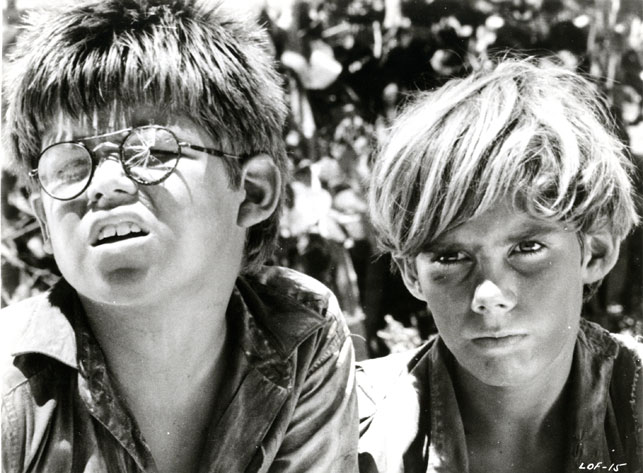

Photo: Lord of the Flies. 1963. Great Britain. Used under Fair Use license.

I wrote this essay for POL 326: International Relations Theories, taught by Dr. Eleanor Morris. This was one of my first attempts to intentionally combine my gender studies work and international relations work, which is demonstrated through my extensive use of prominent IR feminist J. Ann Tickner. Throughout my research for this assignment, I investigated feminist international relations, though for the purposes of the assignment I only incorporated Tickner. This would go on to influence my treatment of the state and traditional notions of it in my future IR scholarship.

Lord of the Flies attempts to argue that, should a band of children be placed on an island and left to themselves, they will enact a realist’s prediction of a war “of every man against every man” (Hobbes 76). The film makes its case by portraying violence and chaos as an inevitable reality. Using realist premises like anarchy (the children have no authority higher than themselves) and self-interested and competitive actors, Lord of the Flies presents itself as an objective account of a simple reality. Rather than convincing a viewer of the viability of realism, however, Lord of the Flies ultimately reads as a self-defeating repetition of the theory’s most basic tropes. This paper will utilize a feminist approach to examine the realist themes of objectivity, rationality, and power that the 1963 adaption of William Golding’s fictional book displays. After a thorough examination of the character dynamics and visual elements, a feminist viewer can conclude that Lord of the Flies’ thesis is not persuasive because it is universalizing and androcentric, and in fact serves as a stark warning against the implications of realists’ masculinist beliefs.

While there are many components to any film, my analysis will focus on the ruling style of the character Jack and his relationship with the feminized characters Ralph and Piggy, as well as the way that the film itself was shot. Comparing the leadership of Jack with the values of Ralph provides insight into the masculinist biases inherent in realist theory. As such, the major segments of the film that allow us to explore realist perceptions of objectivity and rationality are the portions where either Jack or Ralph are firmly in control of large numbers of boys. For the analysis of Jack’s leadership, I will use the bonfire-turned-murder scene where the boys are seen dancing, chanting, and finally killing Simon, the scene where Jack observes one of his cronies spanking a naked boy, and his hunt for Ralph as evidence of a masculinist definition of power. To explore Ralph’s reign, although it was relatively brief, I will pull from the initial moments of his leadership where he distributed labor and created a plan for escape from the island. In these two different segments of the film, the mood and tone is drastically different. Under Ralph, the boys are healthy, hopeful, and hardworking. Jack’s work, however, is marked by hunting and horror. By analyzing primarily scenes where large numbers of boys are present, I am able to observe the group dynamics produced by both styles of leadership and see how realist theories play out as a result.

Realists presume a standard of objectivity, and Lord of the Flies does the same. Morgenthau defines realists’ core values of power and reason as inherently objective and stable (15). The cinematography of Lord of the Flies attempts to replicate these definitions by defining its own narrative as objective and stable. Throughout the film, although many perspectives and actors are introduced and followed, the camera remains a supposedly neutral third party. One person or group is never followed entirely, and the camerawork never fully allows the viewer to grow too immersed in one perspective. For example, in the bonfire-turned-murder scene, viewers are jolted from chaotic scenes of frenzied dance to Simon’s quiet expedition to examine the supposed lair of the Beast. This attempt at providing a totally objective view ultimately renders any attempt at real perspective useless. Later, the film uses this against the viewer by forcing us to watch Piggy’s attempt to reconcile with his participation in Simon’s murder. Piggy’s denial of blame as he cries out, “It wasn’t [murder]… The dance made us do it!” seems absurd and irrational when compared to the “objective” view of his participation that the camera provided us with just a few moments earlier. At this moment, Lord of the Flies mimics the stability and objectivity touted by realism. Piggy is a feminized subject in the film, as will be discussed further, and this attempt at discrediting his fractured narrative further serves to advance masculinist tropes of objectivity and rationality.

Realism’s emphasis on a universal rational actor who single mindedly pursues power is another tenet that Lord of the Flies unabashedly embraces. Morgenthau argues that one can determine how a politician will behave when confronted with a problem by first “presuming always that he acts in a rational manner,” then asking “what the rational alternatives are from which [the] statesman may choose” (15). From there, determining foreign policy is simply a matter of ranking one’s preferences based on how they serve state interest. As such, examining this process of prioritization is critical to determining who is a rational actor and why. By examining the characters of Jack, Ralph, and Piggy with a feminist lens, one can see where the film explicitly encourages the prioritization of masculine values, mirroring realist theory. In J. Ann Tickner’s work “A Critique of Morgenthau’s Principles of Political Realism,” she examines how masculine and feminine actors define power. Masculine power is described as power as domination, which mirrors realist assessments of survival (Tickner 26; Morgenthau 16). Through the character of Jack, we see the results of using power defined in this way. His leadership is characterized throughout by violence: violence against boys within his group, violence against boys who refuse to join his group, and violence against animals and nature itself. In a particular scene, Jack watches as one boy in his group is switched on his behind while lying naked on a rock. Jack also appears to see no issue in murdering Simon; there is no wavering or fussing as we see in Piggy’s brief moral crisis. Jack’s single minded approach to domination is also evident in his behavior towards Ralph. Even though Ralph is no threat to Jack by the end of the film, Jack is so focused on achieving domination that he is determined to destroy him. This abstraction from reality is evident in Jack’s other decisions. For example, at the beginning of the film Jack prefers to focus on hunting and obtaining domination over the island, rather than Ralph’s suggestion that they think about how to get out of the situation. Jack’s decision seems shortsighted, but masculinist psychology and realist theory praises him. Abstract thinking is ranked highly by Lawrence Kohlberg as a sign of advanced moral development and realist theorists often endorse the use of violence for the furthering of state interests (Tickner 25; Donnelly 95).

On the other hand, feminist international relations scholar J. Ann Tickner argues that these leadership decisions are masculinist. By comparing Jack to his opposition, we can examine the way that Ralph and Piggy are constructed as feminized subjects by the film’s “objective” view. In concert with other scholars, Tickner notes that a feminine approach to power defines it as mutual enablement (26). This is evident in Ralph’s leadership style. In the scenes after he is chosen as the group’s leader, we see that he focuses on fairly distributing the labor and even finds a relatively important job for Jack to do: tending the fire that he argues is their way off the island. This contextual thinking is essential to Ralph’s character; he thinks very intentionally about reestablishing their connections to others who are off of the island and is reluctant to get wrapped up in distractions like the Beast. Ralph is focused on where the group is at that moment and how to get them to a better place, and is determined to include everyone, even those he disagrees with, on this journey. On page 25, Tickner summarizes Carol Gilligan’s argument that this form of reasoning is devalued by masculinist assessments of thinking, saying that psychologist Kohlberg fails to consider the way that feminine subjects are socialized to think about problems. Interestingly, women’s contextual approaches are remarkably similar to Ralph’s decisions. Piggy is another character who serves as a foil to Jack’s masculinist violence. Through fatphobic jokes and remarks, Piggy is associated throughout the film with unathleticism and weakness, both of which are clearly aligned with femininity in Western culture. Under Ralph’s command, however, he also symbolizes another distinctly femininized aspect of Western society: the family. Piggy is often placed in the role of caretaker for the younger children. He is seen telling them stories of his hometown, emphasizing both domesticity and narrative thinking. In the same passage where she questions Kohlberg’s hierarchy of moral decision making, Gilligan notes that women are trained to think in narrative ways (Tickner 25). With this in mind, it becomes clear that both of these young boys are feminized, especially in comparison to Jack’s aggressive masculinity. Because Ralph and Piggy’s values are ultimately defeated by Jack’s domineering rule, there is no space for feminine prioritization of decisions in Lord of the Flies. This portrayal mirrors realism’s assessment; there is no consideration of feminine perspectives in this major international relations theory (Tickner 27).

Lord of the Flies attempts to convince its viewer that even the most civilized young men can become violent and chaotic when given the opportunity to let their natural humanity take control. The ultimate destruction of the island is the most persuasive element towards this end. Realism has been criticized for being negative and self-defeating; as the forest burns in the background during the final scenes of the film it is hard not to agree with this (Donnelly 104-105). From the beginning this destruction seems inevitable. The film opened with swelling drum beats that mirrored the frenzied chanting of the boys in the bonfire scene that occurs later on. These visual and audio cues attempt to convince the viewer that this chaos and violence is simply unavoidable, and this realist rhetoric can be easy to swallow. Less persuasive, however, is the very existence of Ralph and Piggy. By setting up these foils to Jack, the filmmakers inadvertently envision the possibility of a different world. Ralph’s contextual, practical thinking and Piggy’s caring, domestic nature may be discredited by realist theories, but they are an alternative. Even when they are being hunted by Jack, they don’t attempt to make weapons. They continue to try to compromise and seek rescue from outside sources. By acknowledging their characters, the filmmakers create an opportunity for envisioning a better world that is not found within traditional realism. The film leaves a critical viewer wondering what would have occurred if there had been a few more Ralphs and Piggys, instead of Jacks. Tickner wonders the same thing, arguing that feminized subjects, such as women, should be more represented in the international relations world and should be respected for their distinctly feminine contributions (30).

It is this nagging question that leads me to conclude that Lord of the Flies is not a persuasive argument for the viability of realism. On the contrary, this adaptation of William Golding’s 1954 novel should prompt its viewers to reevaluate the underlying assumptions regarding power, rationality, and objectivity that both realists and Golding seem to espouse. As seen in the differences between Jack and Ralph’s leadership styles, decision making is anything but objective. While both actors may have been behaving rationally in order to obtain power for the purposes of survival, it became very clear that they defined power differently. Jack’s more masculine definition of power was encouraged by this film and espoused as inevitable, while Ralph’s feminized approach was discredited. Ultimately, this exposes realism’s masculinist roots and prompts critical viewers to ask why we should accept a partial account of humanity, no matter how objective it claims to be.

Works Cited

Donnelly, Jack. “Twentieth-Century Realism.” Traditions of International Ethics, edited by Terry Nardin and David R. Mapel, Cambridge University Press, 1992, 85-111.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. 1651.

Lord of the Flies. Directed by Peter Brook, Continental Pictures, 12 May 1963.

Morgenthau, Hans. “Six Principles of Political Realism.” International Politics: Enduring Concepts and Contemporary Issues, edited by Robert J. Art and Robert Jervis, Columbia University, 12th ed., 15-21.

Tickner, J. Ann. “A Critique of Morgenthau’s Principles of Political Realism.” International Politics: Enduring Concepts and Contemporary Issues, edited by Robert J. Art and Robert Jervis, Columbia University, 12th ed., 21-32.