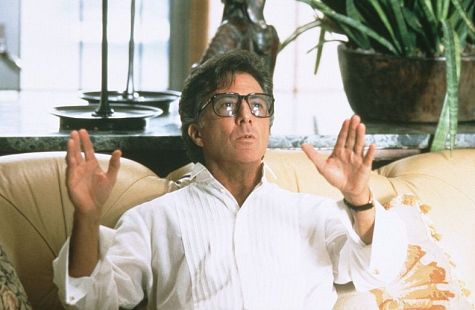

Photo: Wag the Dog. New Line Cinema, 1997. Used under Fair Use license.

In the spring 2020, I wrote this short film analysis for POL 326: International Relations Theories, taught by Dr. Eleanor Morris. Drawing on my knowledge of constructivist and realist international relations theories, I argued for a critical reading of the film Wag the Dog‘s limited contributions to international relations theory. Looking back, I see how this paper laid the groundwork for some of the interventions contained in my forthcoming senior thesis, where I continue to question the role of the state in the discipline of international relations. As a (perhaps obvious) note: this essay includes spoilers to the film discussed therein.

Wag the Dog focuses on the ways that soft power, weaponized by the state, manipulates public support for foreign and domestic policy. The plot follows a spin doctor, Conrad Brean, and a filmmaker, Stanley Motss, who create “the appearance of a war”, to invoke Brean’s words, in Albania in order to ensure that the current U.S. president is reelected. As both Brean and the film continually remind us, truth is all but irrelevant in this shifting political landscape. One might infer that a film with such a flippant attitude towards objective fact would align itself with constructivism, but closer examination reveals that their similarities don’t extend much further. On the contrary, by adopting a perspective exclusive to rich, white, and powerful agents of the state, Wag the Dog fails to acknowledge the multiplicity of realities and norms that constructivism endorses. The 1997 political movie makes a disheartening thesis wrapped in movie magic: the state utilizes diverse and diffuse power relations to shape our reality and any attempt to resist is futile. The film co-opts constructivist arguments regarding soft power, but a more critical constructivist viewer finds its inability to rethink the state deeply concerning. In fact, as I will explore in this paper, Wag the Dog continually reverts back to traditional realist principles in order to make its argument.

In order to analyze Wag the Dog from a constructivist perspective, I am going to focus on the primary characters and the way that they interact with the “outside world” throughout the film. I will specifically examine the ways that social movements and popular culture were shaped by Motss and Brean’s actions by discussing the use of shoes to support the state’s mythical war hero William Schumann. Finally, the film’s closing sequence, where Motss’ death, the president’s reelection, and the Albanian terrorist organization’s responsibility for the bombings are disclosed, will be used as evidence to prove the futility of resistance in the film. These particular aspects of the movie will help address both parts of my argument. First, I will use the way that the film is shot, the plot, and the aforementioned shoe scenes to demonstrate how Wag the Dog co-opts constructivist arguments and language by endorsing subjectivity and soft power that works through popular culture. In the second half of the evidence section, I will contrast the film’s concluding thesis and portrayal of social movements with true constructivist logic. Incorporated into this will be a brief analysis of what parts of Wag the Dog support the film’s portrayal of state power and what parts introduce doubt to its conclusion.

At first glance, Wag the Dog appears to draw heavily on constructivism. Nearly the entirety of the movie is shown from the perspective of the main character, Conrad Brean. No attempt at objectivity is even hinted at; any glimpse we get of the outside world is through television and radio broadcasts, phone calls, and personal conversations that Brean has with others. He watches his stunts play out on live television at the same time we do, crowded around a TV set with Motss and Winifred Ames, his neurotic sidekick, or tuning into a radio station. As he orchestrates the “appearance of a war,” it becomes remarkably clear that perspective is essential to the events that unfold. The American people are experiencing one reality as they watch a child flee Albanian terrorists, the child herself is confusedly clutching a bag of tortilla chips, and the Albanian government is fiercely denying that any such action has occurred. A key constructive concept, “difference across context rather than a single objective reality,” is an integral part of the film’s plot as Brean, Motss, and Ames perform a war into existence (Fierke 189).

A war with Albanian terrorists that do not exist cannot be created alone, however. A second tenet of constructivism that Wag the Dog displays is its focus on regulative, constitutive, and prescriptive norms, and the ways they impact one’s behavior (Finnemore & Sikkink 891). Constructivists often focus on norms, as they have been ignored by the material ontological approach favored by realists and liberals (Finnemore & Sikkink 890). Completely outside of any legal code or specific instructions, we watch as high school students fling their shoes onto a basketball court in support of a brave, lost military hero. Shoes take on extreme political significance as homage to Schumann and become a social movement in their own right. Norms that construct military service members as worthy of reverence, regulate and suppress anti-war opinions and speech, and endorse dramatic shows of support from the American people allow the shoes to have such a large impact. These norms are at different stages of development, or institutionalization, but they nonetheless impact people’s behavior and generate social approval, which is defined by constructivists Finnemore and Sikkink as the most important quality of norms (891). Similarly, a fabricated history is invoked to justify the American people’s support for Schumann, as a song thought to be from the 1930s is used as a rallying cry for “Old Shoe.” No one questions what Schumann did to end up behind enemy lines, nor at this point are they questioning who the enemy is or why the war is occurring at all. Through the use of shoes as a rallying point for Americans, we see how popular culture and social movements are weaponized by the state to create and enforce pro-war norms in Wag the Dog.

Despite this appearance of constructivism, Wag the Dog falls back upon more realist assumptions in order to make its conclusion. The sequence that wraps up the film is clear evidence of this; we see that the U.S. president is re-elected and Motss has been killed in order to protect the campaign that put him there. The viewer is left with the sinking realization that even though none of the “war” ever really happened, no one is left to prove it. The state has absolute power over the reality we experience, and nothing that we can do can change that. The film is filled with evidence of this, and the most chilling part of it is that there is no real proof that the same does not happen in actuality. (In fact, just a month after Wag the Dog’s release, President Bill Clinton was accused of sexual misconduct with an intern and his administration bombed a pharmaceutical company in Sudan, prompting many to draw parallels (“Wag the Dog Back in Spotlight”).) There are two realist principles that become clear in the film’s final scenes. First, the state is the primary actor in international relations and in the movie; only the actions and perspectives of agents of the state are shown to have an impact on reality (Waltz 38). Secondly, humans have a basic nature that cannot be changed; most of the characters behave selfishly to advance their interests with little regard for how it affects others (Morgenthau 15). When Winifred Ames questions Brean about his choice of Albania as an enemy, asking, “What did Albania ever do to us?” he retorts, “What did Albania ever do for us?” (emphasis added). When Motss discovers that news reporters are attributing the President’s success to old campaign ads instead of the producer’s work orchestrating a war, he flies into a rage and demands credit because he believes he deserves recognition for his work. As evidenced by these interchanges, in the world of Wag the Dog, humans are self-interested above all else, even issues of national security, in the case of Motss, and others’ lives, in the case of Brean.

Though this paper does not purport to examine the intricacies of a coexistence between realism and constructivism, (of which there would surely be many), one can safely assume that at least these two principles are in opposition to constructivist logic. According to International Relations Theories, constructivists stress mutual constituency, arguing that there is just as much space for individual actors to influence the state as there is for state power (Fierke 191). In Wag the Dog, the individual actors that we see are all behaving in the interests of the state. Though social movements and popular culture are used in the film, they are only seen weaponized by Brean, acting on behalf of the President. The film misses an opportunity to think creatively about power that pushes back on the government’s influence. Constructivists also explicitly reject the concept of a static human nature, instead thinking of people as “social beings” (Fierke 190). People develop their interests in tandem with their identities, and these are deeply embedded in a social context (Fierke 191). Constructivists argue that Brean, Motss, and Ames’ choices are due to a complex enmeshment of culture, socialization, and norms that affect their rationale. Wag the Dog does not consider these factors, however, opting instead to portray its characters’ behaviors as rationally selfish and power-hungry without a discussion of additional motives or decision-making.

There are aspects of the film that more successfully incorporate these strands of realism than others. State power is actively employed throughout the entirety of Wag the Dog, and as noted, there is no discussion of social movements or norms that exist outside of the state. The final scenes cement the state as the only influential actor in Wag the Dog’s universe, having achieved its power through relations that permeate all society. Less convincing, however, is the usage of William Schumann’s character. Portrayed by Brean, Motss, and Ames as a war hero who tragically died after being trapped behind enemy lines in Albania, in actuality he is a convicted rapist who depends on antipsychotic medication. These two descriptions seem irreconcilable, yet a constructivist might see this as a chance to question the seeming self-evidence of categories like “hero” and “felon.” Considering the high rates of sexual assault and mental illness in the military, it seems absurd to categorize those who are “villains” in a prison jumpsuit as “war heroes” in a leopard-print beret (U.S. Commission on Civil Rights; National Council for Behavioral Health). The existence of this controversial character invites a deeper consideration of who is socially constituted as deserving of respect, while questioning the basic assumptions of our country’s military and prison industrial complexes. Though the scope of my argument does not allow for me to pursue this further here, it is worth mentioning as an aspect of the film that encourages constructivist thought and fails to argue for absolute state power. William Schumann’s characterization epitomizes the complex, contradictory ways that power relations form social beings, and he is one of few characters who exists outside of the wealthy, powerful agents of state power who otherwise dominate the screen.

Wag the Dog offers an unremarkable statement on state power dripping in a sarcastic flippancy reminiscent of only the most shallow interpretations of constructivism. Employing rapid dialogue and an ever-shifting plotline, the film co-opts constructivist beliefs about truth in order to convince the viewer of the futility of resistance. Rather than rethinking the state in the tradition of constructivist thinkers, Wag the Dog merely expands its role and influence without giving individual agents any of the same treatment. The film accommodates theorizations of soft power without reframing the state by incorporating them into a more realist framework. Though Wag the Dog may not be categorized as strictly realist, it certainly falls back on realist principles more than constructivist theories to make its final conclusion: state power is absolute and permeates all social relations. Ultimately, it leaves a constructivist viewer unconvinced due to the realities of social ontology it neglects. Without space for mutual constitution and individual resistance, Wag the Dog is simply a watered down rendition of the theory’s most basic observations and fails to enact an original conclusion.

Works Cited

Fierke, K. M. “Constructivism.” International Relations Theories: Discipline and Diversity, edited by Tim Dunne, Milja Kurki, and Steve Smith, Oxford University Press, 3rd edition, pp. 187-204.

Finnemore, Martha & Sikkink, Kathryn. “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change.” International Organization vol. 52, no. 4, 1998, pp. 887-917.

Morgenthau, Hans. “Six Principles of Political Realism.” International Politics: Enduring Concepts and Contemporary Issues, edited by Robert J. Art and Robert Jervis, Columbia University, 12th ed., 15-21.

National Council for Behavioral Health. “Veterans.” https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/topics/veterans/

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. “Sexual Assault in the Military.” September 2013. https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/docs/09242013_Statutory_Enforcement_Report_Sexual_Assault_in_the_Military.pdf

Wag the Dog. Directed by Barry Levinson, Baltimore Pictures & TriBeCa Productions, December 17, 1997.

“Wag the Dog Back in Spotlight.” https://web.archive.org/web/20120915020805/http://articles.cnn.com/1998-08-21/politics/wag.the.dog_1_people-from-terrorist-activities-dogs-military-strikes?_s=PM:ALLPOLITICS#

Waltz, Kenneth N. “The Anarchic Structure of World Politics.” International Politics: Enduring Concepts and Contemporary Issues, edited by Robert J. Art and Robert Jervis, Columbia University, 12th ed., 33-51.