I wrote this short essay in the Fall of 2019 for WS 110: Intro to Queer Studies, taught by Dr. Lauran Whitworth. The purpose of this assignment was to analyze an archival object using assigned course readings. By using a piece of art created by an incarcerated trans woman who I am friends with, I began my first real trans studies work by uniting scholarship with lived experience. This combination is something that I continue to stress in my current scholarship. This essay was later chosen by Dr. Whitworth to be used as an example for high-quality work in this assignment.

As a trans woman incarcerated in a men’s prison, Naughtia Merrill’s life is “administratively impossible,” meaning that there is no space for her to exist within the system’s gendered framework (Spade 32). Seeking community, however, she made efforts to connect with other trans folks through Black and Pink’s prison pen pal program in 2016. Three years later, she created the work Photo Feature and mailed it to me, a trans student who is not currently incarcerated. This correspondence between two trans people adds an element of community to what was otherwise a sample of personal scrapbooking; Photo Feature reveals to its viewer the humanity and reality of trans imprisonment. Situated in this trans history of criminalization, correspondence, and community, Photo Feature showcases Naughtia’s resistance to the state’s erasure of trans bodies, making this personal form of self-expression an act of radical defiance.

“Trans people are told by the law [and] state agencies… that we are impossible people who cannot exist, cannot be seen, cannot be classified, and cannot fit anywhere” (Spade 41). In Normal Life, Dean Spade describes the ways that administrative law creates population-level interventions that racialize and gender individuals as a nation-making exercise (143-144). The gender binary is one of these nation-makers, as its existence renders trans people’s lives a political impossibility. One of the places where administrative law is most keenly felt is in prisons. They are mandatory, sex-segregated, and already “enormously violent” (Spade 147). Incarceration is particularly dangerous for trans inmates; nearly 78% of incarcerated transgender, nonbinary, and Two-Spirit respondents to a survey conducted of inmates reported emotional pain that stemmed from hiding their gender identity throughout the sentencing and incarceration process (Lydon, et al). LGBTQ+ prisoners are over 6 times more likely to be sexually assaulted while in prison than other prisoners (Lydon et al). Furthermore, attempts to cut down on sexual assault in prisons, such as the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), are rarely successful because they lend more power to prison staff. In some prisons, PREA is invoked to punish those who violate gender norms (Idaho Department of Corrections 5). Trans people are incarcerated in a system of “laws and policies that produce systemic norms and regularities that make trans people’s lives administratively impossible” (Spade 32). As a result, they are continually erased and exposed to violence that shortens their lifespan.

This erasure in the criminal punishment system is particularly salient because trans people are especially criminalized. In Transgender History, Susan Stryker recounts trans woman Virginia Prince’s 1960 conviction of distributing obscenity through the US mail by exchanging sexually explicit correspondence with a “male cross-dresser” (69). Founder of the Foundation for Personality Expression and Transvestia magazine, Prince was criminalized for “using the mail while transgender” (Stryker 77). Stryker recounts the political significance of these criminal proceedings, noting:

As the Prince prosecution demonstrates, the state’s actions often regulate bodies, in ways both great and small, by enmeshing them within norms and expectations that determine what kinds of lives are deemed livable or useful and by shutting down the spaces of possibility and imaginative transformation where people’s lives begin to exceed and escape the state’s uses for them. (Stryker 70).

This quotation explains why trans people’s bodies, social relationships, and even private correspondence have been subject to surveillance, investigation, and criminalization for decades; theirs are seen as unlivable and un-useful lives. In this chapter on transgender history, Stryker weaves a narrative that combines legal and social practices designed to police nonnormative gender expression, medical and scientific efforts to define and “remedy” trans experiences, and the personal stories and activism of several trans and gender non-conforming individuals. Virginia Prince’s story is just one of the ways that trans people are harmed by the state’s regulation of certain bodies.

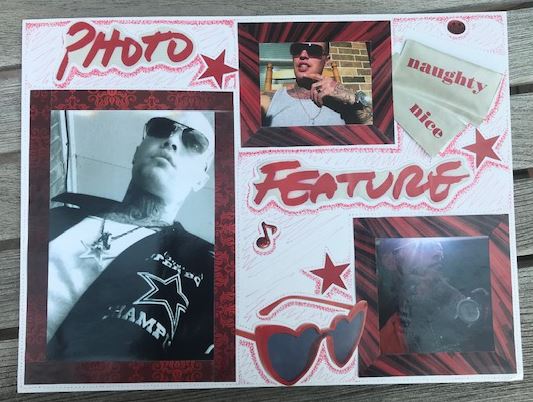

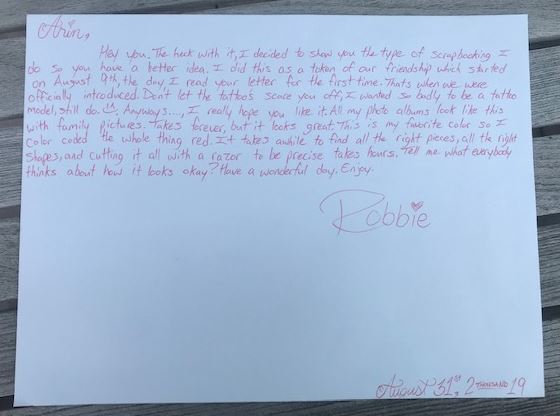

By analyzing Photo Feature in this historical context, we can better understand not just Naughtia’s art, but the lived experiences of thousands of trans people in the U.S. today. Photo Feature showcases multiple photos of Naughtia Merrill. Notably, none of these appear to have been taken in prison. Instead of a uniform jumpsuit, Naughtia wears her favorite sports team’s gear and shows off her many tattoos, showcasing different facets of her identity (Merrill). The brightly colored cut-outs and dotted outlines, painstakingly created with a straight razor and a ballpoint pen, communicate more of Naughtia’s personality; she writes on the back, “This is my favorite color so I color coded (sic) the whole thing red” (Merrill). One of the most striking elements is the use of a photo of heart-shaped sunglasses, the only distinctly feminine part of the piece (Merrill). Similarly, on the back, Naughtia signs her name with a red heart (Merrill). The accompanying note reveals that Naughtia “wanted so badly to be a tattoo model,” and often creates similar albums with “family pictures,” complicating the narrative that trans people within the prison industrial complex cannot seek viable futures or experience community (Merrill). Naughtia’s reality as a trans woman incarcerated in a men’s prison is one of violence, but Photo Feature reveals that this erasure is not complete.

Photo Feature brings visibility to this trans woman’s experience, even if it doesn’t explicitly document her transness. (One can see that at this point in our correspondence she was still signing her letters with a variant of her legal name to avoid suspicion.) Though incarcerated in a system that denies her existence, she negotiates a space for her art and herself through a prison pen pal program. In the context of Naughtia’s correspondence with another trans person, Photo Feature expands the narrative of trans incarceration by not just bringing attention to the creator’s existence, but introducing community to her experiences. Naughtia’s art becomes not just a piece of personal scrapbooking, but a symbol of a relationship that denies the prison industrial complex its ultimate goal: obsolescence for bodies deemed criminal. Envisioning a future of gender self-determination and community, Photo Feature opens a space for “possibility and imaginative transformation” that is otherwise denied to its creator (Stryker 70).

Works Cited

Lydon, Jason, et al. “Coming Out of Concrete Closets: a report on Black and Pink’s national LGBTQ prisoner survey.” Black and Pink, 2015.

Merrill, Naughtia. Photo Feature. 31 August, 2019. Mixed Media Photo Collage. Sent to Author.

Spade, Dean. Normal Life. 1st ed., South End Press, 2011.

Stryker, Susan. Transgender History. 2nd ed., Seal Press, 2017.

Idaho Department of Corrections. Procedure Control No. 325.02.01.001, Prison Rape Elimination. 2009.